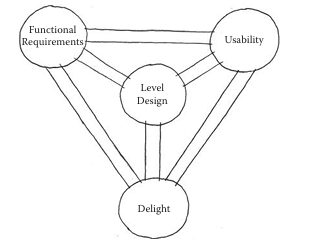

The book An Architectural Approach to Level Design start talking about Vitruvius and his Ten Books on Architecture, a roman architect that proposed in his book some principles that are relevant until today and should be considered to construct any environment in a game. Those principles are equally important for level design that are being proposed:

Firmitas (Functional Requirements) :

“Firmitas, stability. The building stands stable on it’s own” - Martin Nerurkar

“First and foremost, your game must work. This is the firmitas of level design.” - Christopher W. Totten

The minimum expected for any game or level is that it should be playable. A level should be minimally stable and performant enough to be executed from the beginning until the end of it.

Any bug generated, from programming or even level design, can offend this principle by making a certain area of the game unplayable, but I think the major offender of this principle is performance. There’s many techniques to segment a level in a way to keep it performant as the project grown.

Another concept that I think is very neglected by level designers is that from the beginning of the creation of a environment we already can start to think about light, or even better, how the environment shape will be affecting the performance of light. We have some tools that help to think about this like the Light Complexity on Unreal, but understanding the Raycast algorithm is fundamental.

Utilitas (Usability):

“Utilitas, usability. The spaces created by the building are suited for their intended use” - Martin Nerurkar

“Gamespaces must be usable. In this way we should concentrate on how players see gamespace through points of view and game cameras and how one navigates levels. This element of level design concentrates on navigation and teaching. As we will see, levels are an opportunity for game designers to have an indirect conversation with players. As such, our game levels should teach players how to use themselves and speak in easily understood language.” - Christopher W. Totten

A space inside a game should be serving certain necessity that a game has. This is the famous form follows function design principle. A level designer need to be aware all the time what that space is serving for and accommodate that. I also like to think that all the Ten Principles for a Good Level Design are inside this category.

I like to create flow charts and some simple graphs (like a Level Progress Diagrams (LPD) or even a simple bubble chart) considering the requirement imposed by the game primarily, even before we hit any game engine. This way we already can start to discuss how all the requirements a section of the game has, when mechanics should be introduced, how big the space can be and some views.

Venustas (Delight):

“Venustas, beauty. This building has a beautiful aesthetic” - Martin Nerurkar

“Our gamespaces should rewarding to go through. For this we must engage the psychological elements of level design and understand how levels guide players through emotional experiences” - Christopher W. Totten

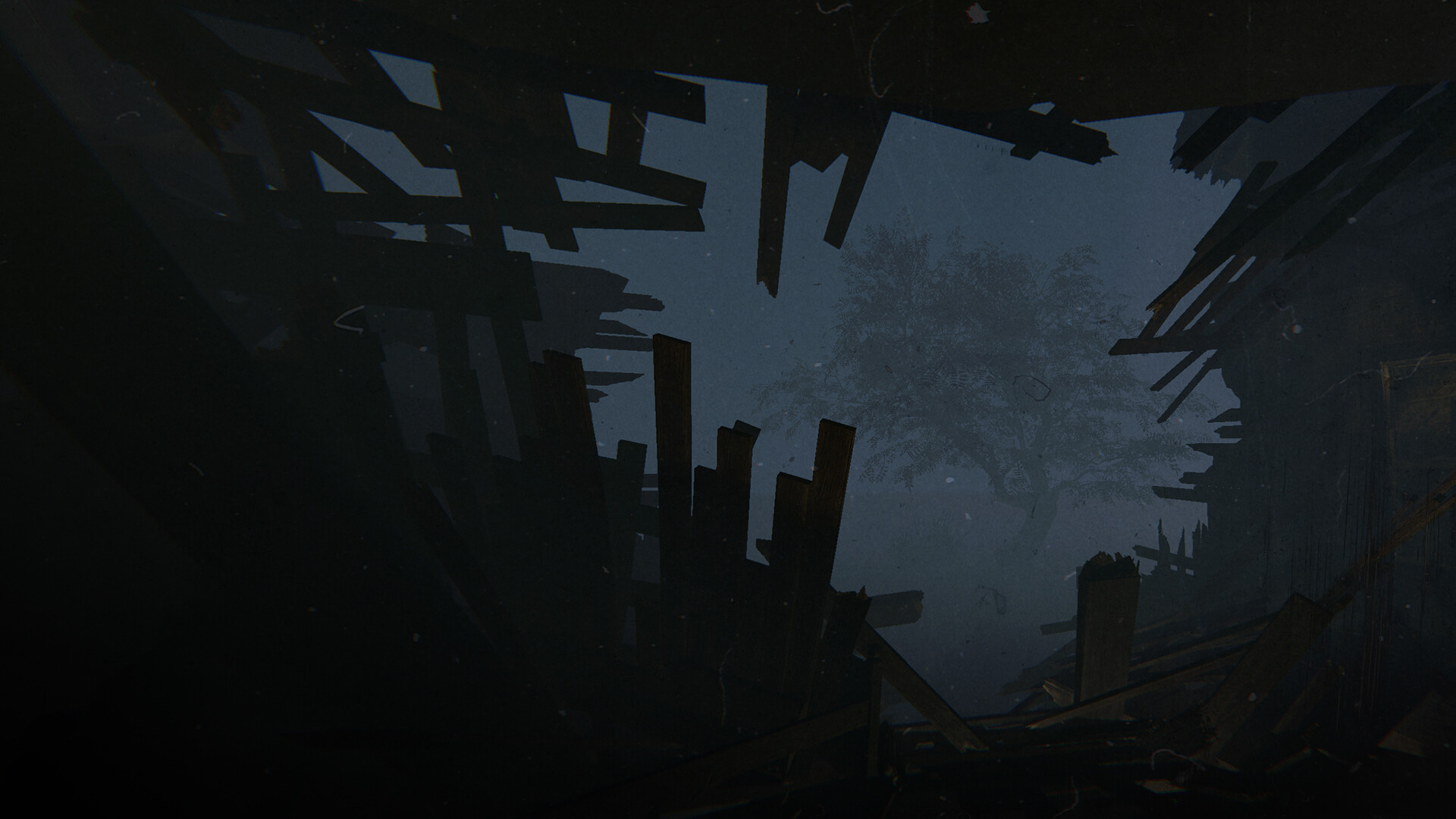

Even that Venustas originally was preach that a building should be easy on the eyes, on level design we are actually reminded that a space should serve the intended atmosphere expected for an area. The level design could be helping by setting the mood of an area with audio visual elements, but it can by nature, help by adding environmental storytelling elements.

A good example of a horror game that deliver environments that are beautiful, yet the environment is destroyed and can be even filth is Phasmophobia. Specially on the new maps, where clearly the team has gained more experience and knowledge, the maps being reworked have many views that capture the players eyes even inside a dangerous ghost investigation

For this matter I really like to reference the importance of readability of a view that usually can be reach by contrast or even by studying some composition techniques like the Rule of the Thirds.